2023 Tarkovsky Prize Honorable Mention: Marlena Rohde

LA DOLCE VITA

by Marlena Rohde

Federico Fellini and Marcello Mastroianni first met on a beach in Rome. Fellini told Marcello that he wanted him for a movie he had begun working on, La Dolce Vita, because Marcello was “the face of normal,” and Marcello asked to see the script. Fellini handed him a folder of pages, all blank except for the first, on which Fellini had sketched a man with an enormous phallus swimming in the sea, surrounded by dancing mermaids. When I learned about this interaction, La Dolce Vita suddenly began to make sense to me. La Dolce Vita follows a journalist named Marcello over seven days and seven nights, as he goes from a cynical observer of the wealthy and famous to one of them. Fellini was influenced by Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, and therefore uses monsters and the subversion of the physical form to make a statement about Marcello. La Dolce Vita uses Marcello’s transformation into a sea creature to criticize his indoctrination into the lives of the wealthy, opening up a broader connection between Fellini’s life and Kafka’s Metamorphosis.

Kafka’s Metamorphosis is about two transformations: the mutation of Gregor Samsa into a bug, and the growth of Samsa’s sister from a girl to a woman. Gregor Samsa, an ordinary traveling salesman, is the sole supporter of his family, until he wakes up one morning as a large insect. Samsa’s family suddenly fears and ignores Samsa, making him compliant and aimless. Samsa’s transformation inadvertently turns his sister, Grete, from a passive girl without passions to the leader of the family. She also dedicates herself to her violin playing, emphasizing her choice to and ability to pursue art, in contrast to Gregor’s hollow career.

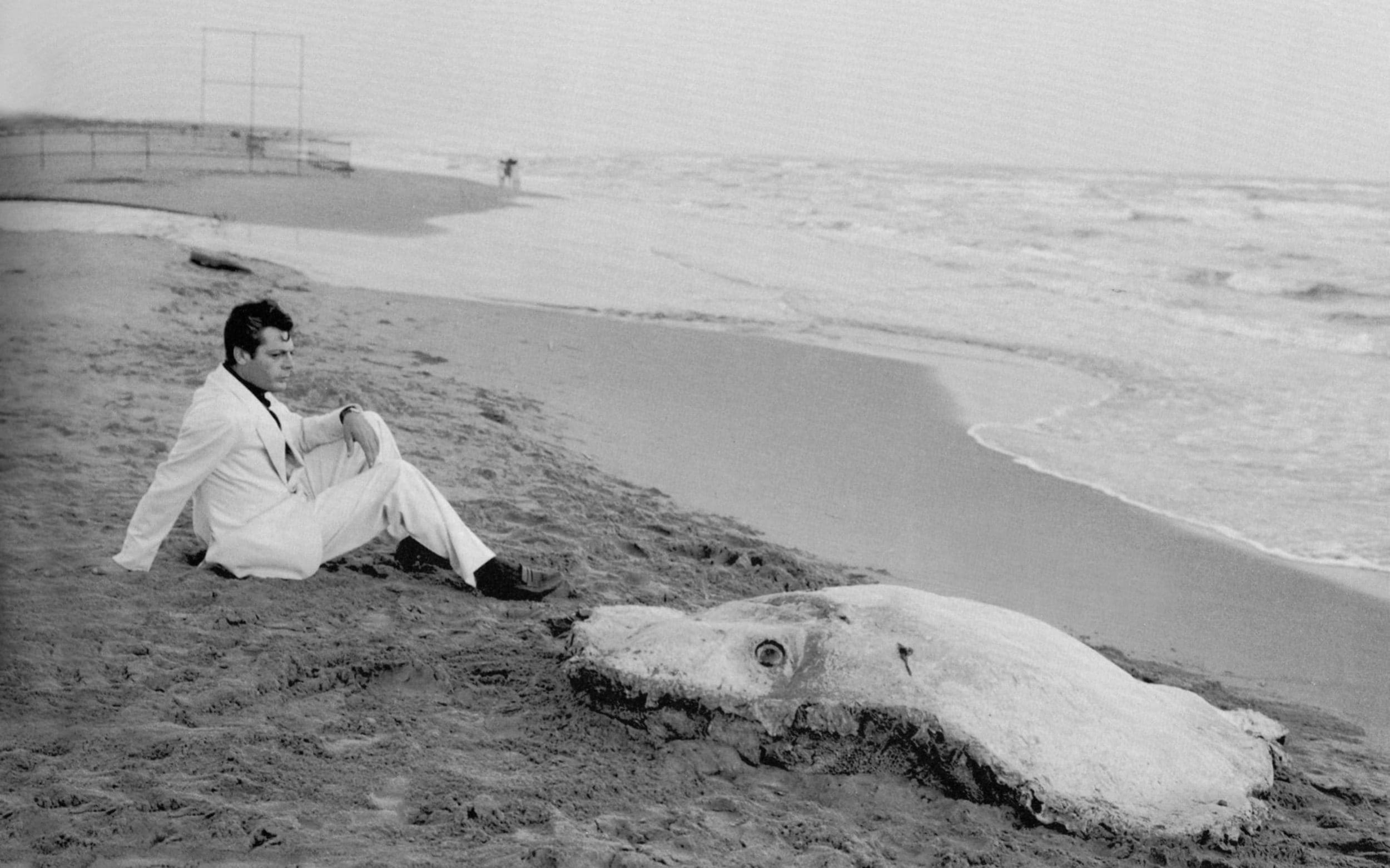

In La Dolce Vita, Marcello undergoes the transformation from man to creature, while Fellini himself undergoes artistic growth that mirrors Grete’s. La Dolce Vita ends with Marcello and the wealthy and famous attendees of an all-night orgy standing around a large sea creature that has washed ashore. “It insists on looking,” says Marcello. Marcello, like the paparazzi and like the audience itself, is unable to turn away from the world of the wealthy and famous. The party picks up the sea creature and carries it home to eat it, and Marcello himself is dragged away from the foreground of the screen, away from the audience, into that inaccessible world. Like Gregor Samsa, Marcello becomes complicit, loses his self sufficiency, in his transformation from man to sea creature, from author and observer to one of them. Like Grete, Fellini seemed to undergo the opposite transformation – he became self-assured and dedicated to his craft. In The Films of Federico Fellini, Peter Bondella writes: “Up to the appearance of La dolce vita, in fact, Fellini's intellectual trajectory seems to be clear: His films begin in the shadow of neorealist portraits of life in the sleepy provinces of Italy, focus upon various forms of show-business types, and ultimately lead toward the capital city of Rome and the "sweet life" of movie stars, gossip columnists, and paparazzi scandalmongers. After that point, Fellini's cinema turns inward toward an overriding concern with memory, dreams, a meditation on the nature of cinematic artistry, and the director's fantasies.” La Dolce Vita was a turning point in Fellini’s career, away from the neorealism that had a grip on Italian cinema, and towards art films regarding his childhood, his dreams, Italian history, and the nature of cinema. After La Dolce Vita, Fellini no longer cared about commercial success. His films became more personal and artistic, with 8 ½, The Satyricon, and Casanova. Fellini blossomed into an artist with his own style and a real belief in his work and its authority.

Marcello interpreted the man with the large phallus, surrounded by mermaids, to be a self-portrait of Fellini. I agree. Fellini himself came from humble parents in the small tourist town of Rimini, and dreamed of going to Rome. By the time he began working on La Dolce Vita, Fellini had been fully incorporated into the empty but glamorous world of the wealthy and famous. In the image from the script, he drew himself as malformed, almost inhuman, and surrounded by people who were glamorous and beautiful but also mythical. Marcello is an extension of Fellini, the dreamer from Rimini who had creative pursuits but didn’t know how to follow them, or how to believe in them. I think that in La Dolce Vita, Fellini was forced to see what he could become, the final stage of his transition in the sea: the washed up sea creature. And I think that by confronting that image, Fellini was able to turn away and begin making art for himself. But the audience insists on looking.