2019 Tarkovsky Prize Honorable Mention: Una Lomax-Emrick

Una Lomax-Emrick (18, Urban School)

The Racket of Consciousness: Three Colors: Red

I recently listened to psychologist Kaern Kreyling describe the ways in which our minds are obsessed with maintaining constant inner dialogues in spite of the fact that silence dominates many layers of our subconscious. The brain and consciousness are vastly silent, she said, but we are often hypnotized by the small flood of doubts, mundane insecurities, philosophical musings, and “Did I remember to turn the stove off?” that crowd the top layer of our thoughts. Amidst our constant media inundations through the devices in our hands, we tend to forget the silence but are still desperately seeking it. We buy into the mythology of a spin class somehow destined to cure anxiety, laud prohibitively expensive “mindfulness retreats” when we could just as well follow a map to a stranger’s home or celebrate an oncoming storm. Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colors: Red presents a stunning portrait of the power of silent human connection in spite of a superficial draw to noise. As Janet Maslin states in her 1994 New York Times review of the film, “Stories develop like photographs in a darkroom. They are sharply defined only in retrospect, when the process is complete.” Kieślowski examines love and coincidence with astounding poise, rendering the observer delightfully complicit in forming the relationships that arise and the hopes that spring in the face of a missed call, a wounded dog, and lost romantic connections. His characters are constantly seeking peace but are unable, until the film’s end, to find the silence that can truly bring them to rest and back to one another. His film is a tremendous testament to the power of connection and the ability of some beautiful, internal grace to guide people to the silence, if they will only pay attention.

The telephone, a central focus of countless scenes in Red is the only real antagonist in the film. It acts as a block between people, a shade attempting to disrupt truth love, and much beauty throughout. Voices become weapons. Valentine’s (Irène Jacob) boyfriend summons her to the perilous waters of the English Channel, and Auguste (Jean-Pierre Lorit) makes plans and loses the woman he loves through the off-white chord of his landline. Their relationships are superficial; Kieślowski implies again and again that in order to love and to understand, one must be physically with someone and, of course, one must be silent. The Judge (Jean-Louis Trintignant) lives a solitary life in a tumble-down house; he is obsessed with the noise of others. Sitting alone in the dark, we watch his mind play out in the rising and falling of voices on his stereo screen. This man is deeply unhappy, not content with the musings of his own desperate mind, he must prey on the voices and feelings others to be satiated, and Valentine is similarly disgusted and enamored of his noise. The night outside is dark and silent. Rita, the sweet dog, is not moaning anymore, she is with the people who care for her and there is safety to be had in the assurance that they will love her. Yet, The Judge and Valentine are isolated. Their friendship springs from this night and the subsequent thawing of their initial icy self-righteousness. Much later on, when they share a drink in the stormy hall of Valentine’s show, there is psychological silence. A beautiful howling of the wind is the only sound amidst their hushed declarations of truth. Their friendship has allowed Kern to find solace in his own mind. He writes letters to his neighbors just as Auguste books passage on the ship to England; they are present, direct, and soulful. This is how the two men finally begin to emerge from the tumultuous cacophony of their heartbreak and into a silent comfort.

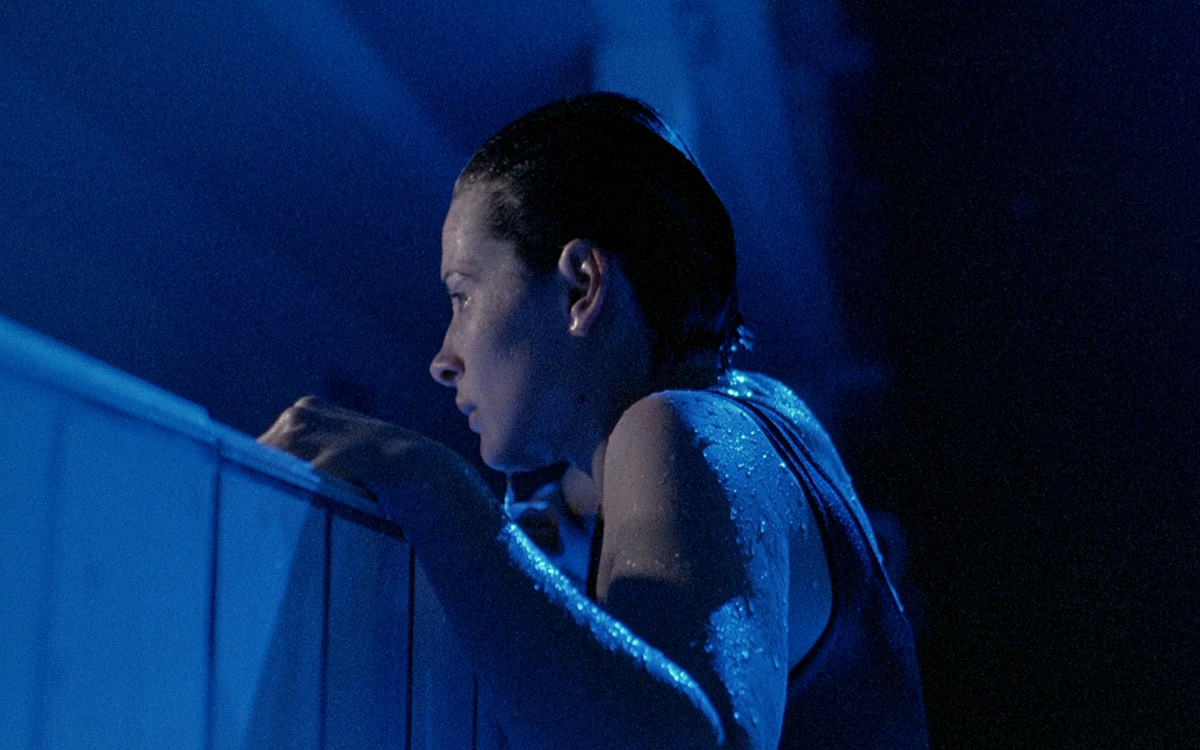

Valentine, in many ways, embodies the kind of delicate self-possession that helps lead everyone back to silence, yet at the beginning of the film, we find her running her to the telephone, to a lover obsessed with the sound of her voice. She is trapped in the scene so brilliantly depicted in the opening credits, in telephones wires echoing across seas, in between walls, and underground. The telephone-world is a dismal place; we know that Valentine’s lover is all wrong, overbearing, jealous, but she sees him and her relationship with the distortion only her black telephone, perched perilously atop red table, can provide. Yet, though she is deceived by loud declarations of “care,” she is ultimately saved by her ability to sit comfortably with her own mind, and indeed, to quiet it down. In a truly spectacular scene, we see her entering the home of a man the Judge has been spying on with the intent to tell him that the Judge knows of his affair. Upon stepping beyond the threshold, she is met by his family and the loudness in her mind pauses, she reevaluates and leaves, understanding and finding peace with the simultaneous serenity and dangers of secrets. Valentine’s beauty doesn’t come from loud poetic declarations; instead, it appears in her ability to effortlessly blow a bubble without question and without laughter. She is not childish or pretentious, merely a woman who knows herself dancing and sweating in a crowded studio, or quietly consulting with a veterinarian in a dimly lit after hours clinic. She epitomizes growth in her melancholy; she ventures out onto the sea and finds quiet in the arms of another. She is human and deeply connected to her home: the little flat across the street from the place she buys a paper and the drive she learns to take in silence.

Silence is Kieślowski’s surprising and absolutely necessary choice for a film entitled Red. There is no screaming in this film. The Judge is no crazed professor, merely a lonely man with a void in his heart and the voice of others dominating his mind. Auguste is loud only in action; boldness and racket only echoing in his agile clambering up a balcony and subsequent confrontation. The telephone does not ring like in some 1950s nightmare film, sounds buzz and tinkle, but never yell. Red is every part of this film, and Kieślowski’s brilliance is in allying such a crimson with a kind of gentleness hardly captured on screen. He explores the lower part of the mind, the kind hypnotized by simple beauty instead of by fear. Soft words exchanged in lamplight and the curve of a narrow drive are the backbone of his picture. Three Colors: Red is a testament to relationships, to subtlety, and to silence.