2025 Tarkovsky Prize Honorable Mention: Phoebe Tan

Mass Media Conglomerate Culture in The Truman Show

by Phoebe Tan

The 1998 film The Truman Show, directed by Peter Weir, is known for being a classic of its time, and continues to be widely known decades after its release date. A large part of its popularity likely comes from the irony of it in a way that makes us wonder if our lives are also constantly surveilled like Truman's, and if anything is real. I took a class called Mass Media and Society this summer, and when I saw the film for the first time, I immediately was able to draw many parallels between Truman's world and ours. The main one was how Christof's relationship to Truman in the film is similar to that of mass media conglomerates to us, their audience, in real life. The Truman Show is synonymous with the fabricated reality presented to us by mass media conglomerates.

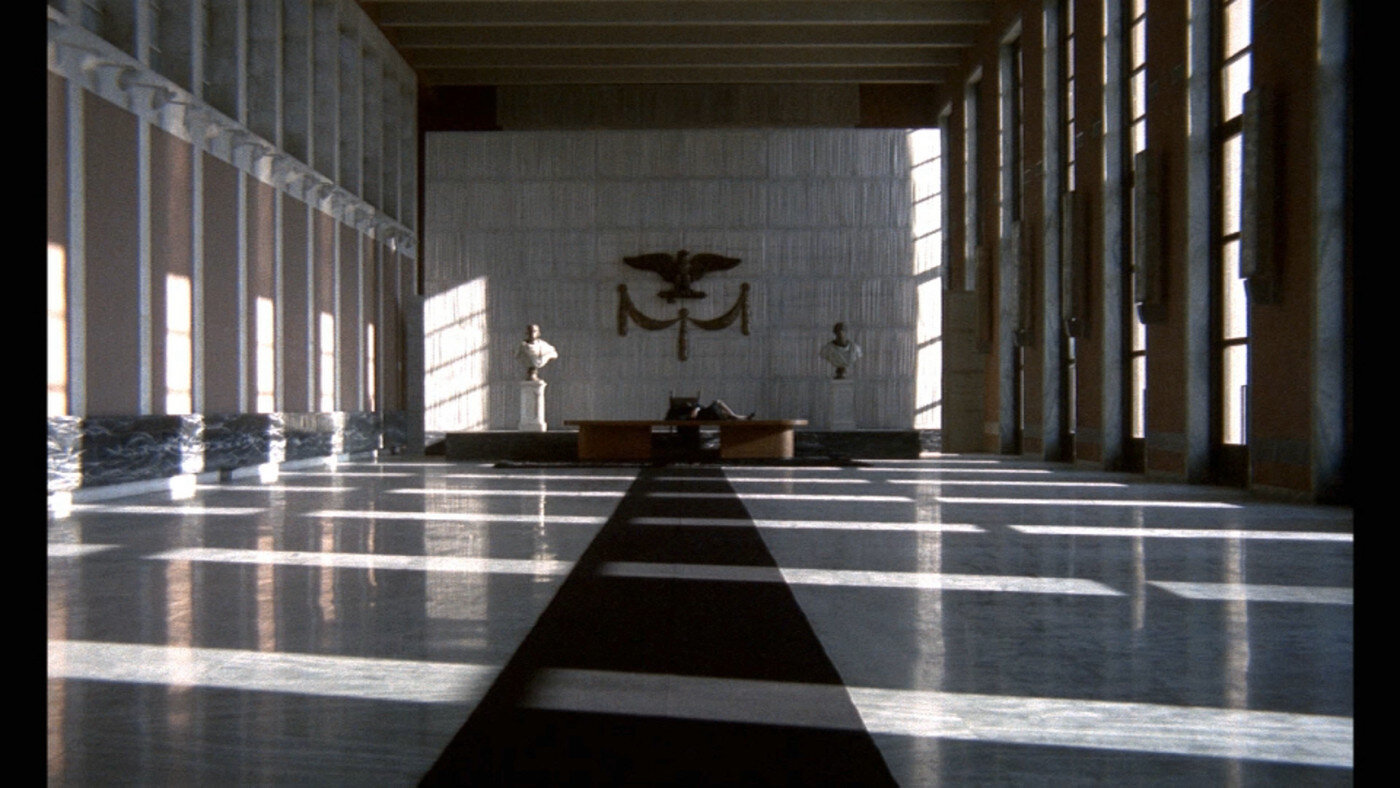

In the Truman Show, Christof is like a mass media conglomerate in real life. Mass media conglomerates are large companies, like Disney, that own many other media companies. There are only six main mass media conglomerates; this means six huge companies control almost all the media we see, from newspapers to movies to social media. If we think about it, it's a very large amount of control in the hands of a small number of people. This is similar to Christof's role in the film. He controls all of what Truman sees and experiences, from the weather to his conversations with his best friend. Christof has a lot of control over Truman's life, similar to the role of mass media conglomerates in our lives. In real life, news companies that lean heavily to either the right or left amplify their audience's thoughts in a way: they say things that push their audience further to the right or left, creating a divide in American politics between the right and the left. Christof, like our mass media conglomerates, also uses Truman the way mass media conglomerates use their audience for personal gain. Christof exploits Truman to make money, even saying that the show generates as much money as a small country. This is similar to companies creating algorithms that are designed to keep their audiences on their websites for longer. By doing this, they can generate more ad revenue and make themselves increasingly more wealthy. Christof's blatant exploitation of Truman made me feel pity for him, but also makes me think about how we should also pity ourselves, then, because we are in the same situation as Truman; being controlled and manipulated by a larger force for their personal gain, at our expense.

Another way our reality is similar to Truman's is the advertising. The advertisement strategies shown in the film, like product placement by Meryl, are also like the advertisement strategies used by media companies in real life. Throughout the film, Meryl strategically advertises several different products, including coffee beans, a lawn mower, and a multi-use kitchen tool. In the beginning, she does it subtly, barely mentioning the kitchen tool's three uses. But over the course of the film, she becomes increasingly more obvious about her attempts to advertise different products, like the coffee beans. It becomes so strange that even Truman questions her about it, asking her who she's talking to. This scene, and the one where she ends up breaking down and screaming for help made me feel fearful for Meryl. This is similar to real life, when we make fun of advertisements that seem to try too hard to sell a product, like the insurance guy who's always getting in some crazy accident. These ads attempt to make us laugh and remember them in a positive way, but more often, they are remembered for being annoying and trying too hard to be comedic. But there are also more subtle examples, like when celebrities use a certain brand of product and that product becomes super popular. In both The Truman Show and real life, companies use our psychology to manipulate us into wanting to buy a product more, which in turn increases their ad revenue.

Seeing Truman break free from Christof's control can be taken and applied to our own lives, where we can escape from the "cage" we're in, created by mass media. For Truman, it was to literally break free from the cage Christof put him in. For us, it is breaking free from being controlled by these large media companies. To stop scrolling on TikTok endlessly, to stop believing everything we see on the internet, and start questioning things. To break free from reality as we know it will be challenging, but is necessary.