Review: FANNY AND ALEXANDER

by Lucy Johns, Art and Film mentor

“Fanny and Alexander,” Ingmar Bergman’s final film, delights not only for its artistry but also for its revelations about the great director’s frame of mind. The consummate explorer of angst affirms here that evil can be punished and fears vanquished. The result is a film more affectionate than analytical, more hopeful than tormented. In the context of Bergman’s body of work, marked by ever more inventive agonizing over the human condition, this shift is an unexpected joy.

The transformation means a new theme, a new dramatic focus, and a new directness. Rather than transmuting his doubts and questions into characters, Bergman delves behind character to explore its origins in the family. In “Fanny and Alexander,” family is the lead and family dynamics is the story. The film conjures scenes of goodness and evil notable for the director’s lack of ironic distance. It radiates a reconciliation with women, typically portrayed by Bergman as the force behind most of man’s anxieties. These explorations wrap around a traditional Bergman assumption: that salvation lies in the creation of illusion. Theater, puppets, magic, even deranged people who see and feel more than normal ones do, can save the most wounded victim. All this in three hours structured almost as a play that echoes “Hamlet” at many points.

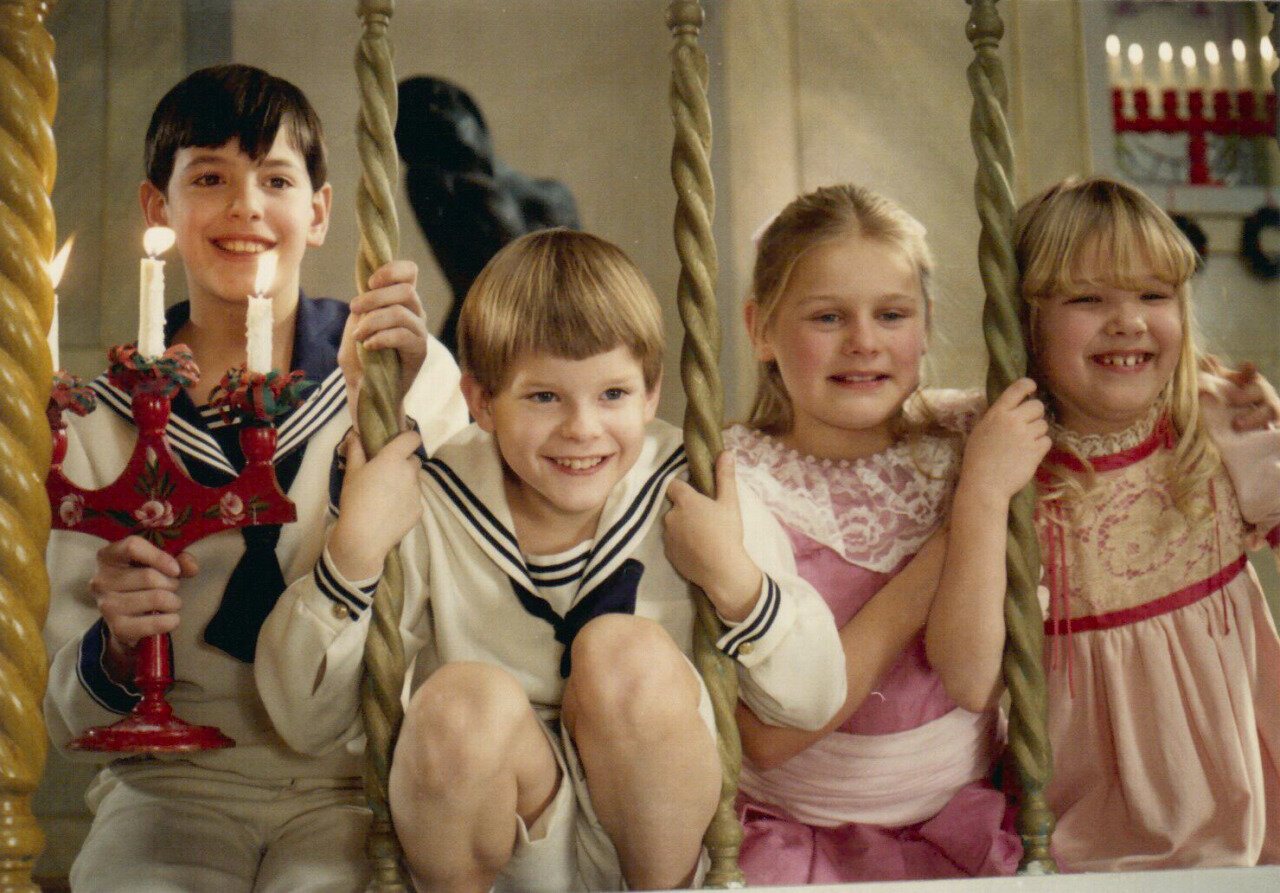

“Fanny and Alexander” divides into two long acts. The first follows a boisterous Swedish family celebrating Christmas a century ago in the sumptuous home of grandmother Helena (Gunn Wållgren, one of Sweden’s greatest actors). Helena is beautiful, rich, and empathetic, unencumbered by class snobbery (the servants eat and play with the family) or ethnic prejudice (an elderly Jew is Helena’s treasured companion in her widowhood). Her three sons embody familiar Bergman crises beneath the brilliant surface. Their financial, sexual, and existential dilemmas are presented, however, with some welcome warmth and humor. Each son is sustained by a much younger wife who shares his anguish and tolerates his avoidance strategy – alcohol, sex, theater - with old-world feminine grace. Fanny and Alexander are energetic siblings in the swirl of humanity filling the house. When their father collapses while playing Hamlet’s ghost, the stage is set for the next act. A life of color and glamour darkened only by typical existential conflicts descends into a hell created by their mother’s remarriage to the local bishop.

Alexander detests this cleric from the first moment. The boy intuits a polished hypocrite, played to perfection by Jan Malmsjö. Alexander and Fanny shrink from his unctuous voice, controlling hand, and barely concealed malice. Alexander spins tales of escape and felonies that are heard by his stepfather as lies, a transgression subject to severe discipline. He gets a horrific beating. The scene evokes inspired film-making. Only female faces are shown: the bishop’s mother, complacent; his sister, complicit; the tattle-tale servant, fearful; and Fanny, powerless. Only the wallops of a willow wand are heard. Alexander is not shown and makes no sound. His repentance, coerced by torture, is smugly accepted as evidence that violence can teach morality. The conflict between these males goes beyond Oedipal. The young Alexander doesn’t so much challenge his father’s usurper as he embodies an innocence that evil, camouflaged in religious rectitude, is determined to destroy.

The use of sound during the beating is one of several scenes where fortissimo noise nails emotional identification to the visuals. A village creek roars, portending catastrophe. Four great draft horses thunder to the rescue over cobbled streets – not quite the Lone Ranger and Silver, but suited for the purpose and time. Screams resound through a silent house, blasting children out of bed to witness uninhibited grief. The crack of elastic branch on bare flesh signifies fearsome brutality. Sound imbues imagery with a power that marks a master at work.

The resolution of the central drama between a boy and his male nemesis is not the only struggle overcome in “Fanny and Alexander.” Several women in the film suggest that Bergman has surmounted some primal male phobias patent in his previous work. An independent grandmother, a redeemed mother, a devoted sister, a ribald servant who yearns to control her life all transcend the patriarchal stereotypes that haunt his films. Grandmother Helena presides over a household whose tolerance and rituals are represented as the only reliable solace there is. Alexander’s uncle affirms this in a long monologue that veers towards maudlin but still seems heartfelt. Alexander’s grandmother and mother murmur happily, “It looks like we’re in charge now.” These scenes convey a peace that feels real for their author. No longer a threat, the women in “Fanny and Alexander” are merely fascinating. The Alexander who grew up and brought so many unhappy females to life on the screen here presents women as beneficent as they are complex. If they signal an evolution of Bergman’s consciousness, they may explain how he produced this masterpiece of indelible, and not at all predictable, humanity.